05: Crestone / Atlantide

On Marnie Ellen Hertzler's Crestone (2020) and Yuri Ancarani's Atlantide (2021), and on male society and group sociality.

“Good night boys. Sleep tight. Sweet dreams.”

Crestone (2020), a hybrid documentary by Marnie Ellen Hertzler, opens with an enticing, enigmatic line of narration. “This movie is a love letter,” says the filmmaker with a whisper. “This movie is about the end of the world.” This sets a tone, though the film that follows is less grandiose than this introduction suggests. Shot in eight days, more love letter than apocalyptic drama, Crestone is a relatively straightforward portrait of a group of self-describing “Soundcloud rappers,” high school friends of the filmmaker who, feeling despondent about the state of contemporary culture and fearful about the future of the planet, have chosen to opt-out of mainstream society. Establishing an autonomous community in the Colorado desert town of the film’s title, they live together in a state that drifts somewhere between blissful aimlessness and nihilistic abjection, time stretching out into infinity as they play video games, grow weed, record songs, explore the desert, and eat baloney sandwiches.

Many things about the men and their interrelations are left purposely undefined by the filmmaker. In ‘Sloppy,’ a charismatic character with face tattoos and a floppy mop of hair, the clan has an ostensible leader, but it's never exactly clear what vision he has beyond vagaries like “peace and positivity.” There are no doctrines, no biographies and no backstories, no real explanations for anything that is going on other than the titbits that Hertzler whispers as narration or the characters themselves reveal through conversation. As a result, there is little sense as to how these men got here, what income sources supplement their lifestyle, or what they might hope to achieve. Instead, the focus is on the connection they share: a simple yet sturdy bond that binds the men with each other and connects them to the earth. Out in the desert they live like gorillas, roaming, eating, playing, picking each other's fleas; thinking not of the future but living in an eternal present, they take each new day as it comes. Crestone has drawn frequent comparisons to the early films of Harmony Korine, but, as Justin LaLiberty notes, the work of Sean Dunne seems an apt comparison. All three filmmakers display a fascination with, and affection for, outlying forms of American idiocy.

Hertzler’s approach with the film is careful. She remains sceptical of the group, but never patronises them or doubts the authenticity of their often contradictory beliefs or motivations. Instead, as she circles the men with her handheld camera, by observing their group rituals, hearing from them one-to-one, and involving them as collaborators in a form of dramaturgy that makes them active participants in their depiction, she establishes a method that sees documentation as a form of play. Working with “the most unreliable characters” any filmmaker “could ask for,” Hertzler plays “a game of belief and disbelief” with the men, probing them to see how much they buy into their own spiel and how much of it dissipates like the clouds of smoke they surround themselves with. Dealing with more volatile subjects, Hertlzer could be playing a dangerous game. She could risk platforming something problematic and seeming uncritical in her approach. Fortunately, these men are docile, always charming and kind. As a result, her tentative distance creates a pleasing ambiguity. At no point is it clear if these men are fools duped by a charlatan high on his own supply or vanguards who have it all worked out, living a pure and pleasurable post-capitalistic lifestyle free of all contemporary concerns.

“I didn’t know what to expect, but from past experiences, I knew not to expect too much” says Hertzler wryly early on in the film, but her ironic millennial tone disguises a sincerity that is essential to her project, a willingness to trust that, as much as they may seem misguided, her friends generally mean well. This mutual sincerity is disarming. “I really fuck with this scene because it’s a real brotherhood scene,” says one of the men as they all stage a sequence that sees the group gaming together in an illuminated cave, connecting over the rejection they felt before and the kinship they feel now. “For a long time we haven’t felt like we’ve belonged anywhere,” one man says, displaying the sort of simultaneous naivete and blunt emotional forthrightness that makes their lifestyle seem so appealing. When Sloppy finally outlines what they are working towards, it sounds like something that most people would want for their own life. “I just want to create a community where we can all live together and grow old, knowing we are surrounded by people who care and love each other with no judgement or negativity.”

As the film goes on, these men start to seem less like dropouts and more like prophets, a group of stoners who have smoked so much that they have seen what lies behind the horizon. Facing a near-future of rising temperatures, food scarcity, competition for resources, and increasing global political intensities, they are already set up with everything they need to survive. Yet, with women absent, this community they have created is either a group with a membership they have no intention of expanding or one that has been established without a great deal of thought. As forest fires blaze unacknowledged in the background of the film, Hertzler’s sardonic assessment of this anarcho-primitivist, homo-romantic society they have clumsily assembled can be read as both criticism and praise. “If the world was ending, they probably wouldn’t even notice,” she says. Looked at like this, their politics may seem simplistic, narrow-minded, and ultimately defeatist too, but it cannot be said to be particularly hostile or unkind. If the world is soon to end, you might as well see out the fateful final days with all your best boys by your side.

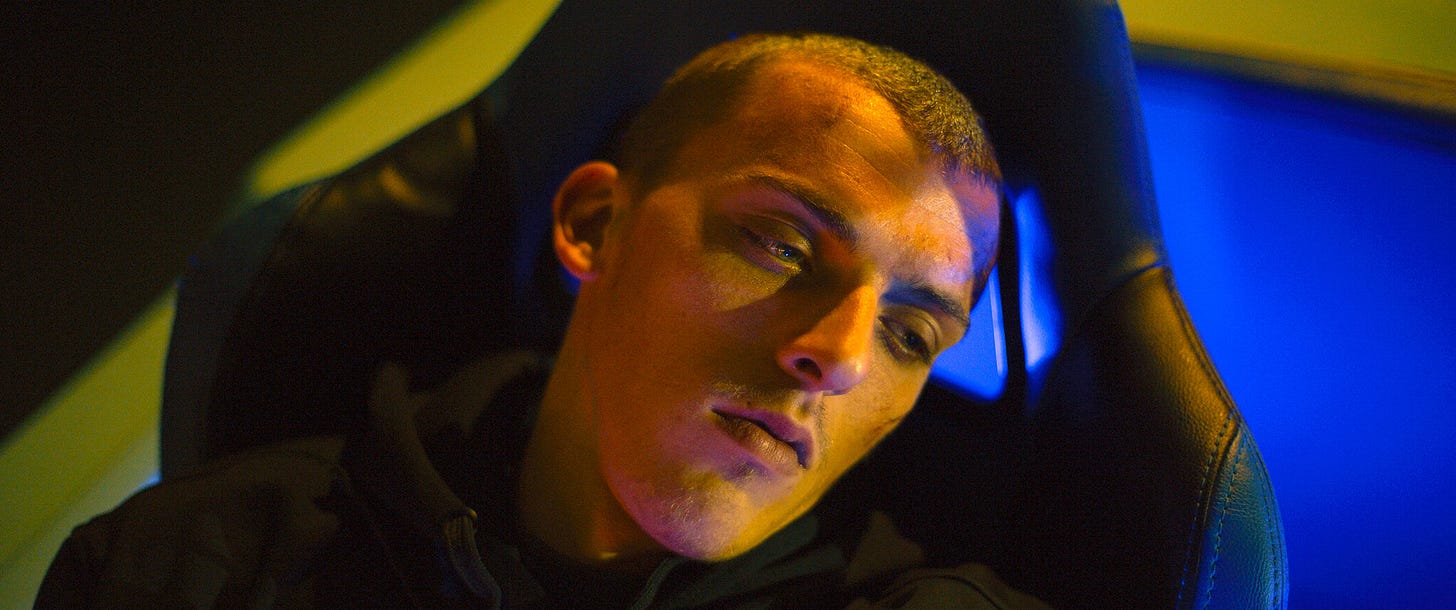

Similar ideas are threaded through Yuri Ancarani’s Atlantide (2021), though the tone of that film is decidedly darker. Another hybrid, the film also focuses on a group of young men existing on the fringes of society, living not in America but Italy and connected not by internet rap music but by speedboat racing. In Atlantide, Ancarani creates an insular, exaggerated vision of a world in which the horizons for young men are so short and the opportunities for escape so few and far between that the only goal in life becomes “to go faster than the others,” a success signified by a km/h notch etched on a leaderboard on a wooden post jutting out of the water. Set within the enclave of Sant'Erasmo, an island on the outer edges of the Venice Lagoon, the film focuses on one young boy racer, Daniele, and his long suffering partner, Maila, a woman who weathers his melancholic moods and frustrated desires in the hope they can find a route out of Sant’Erasmo and build a better life together. Unlike the men in Crestone whose bond seems almost cosmic in strength, Daniele does not experience a sense of belonging within his peer group, only a connection of class and culture that expresses itself mostly through hostility rather than any form of fraternity. Within a group of young men who are already impoverished and alienated, existing on the watery fringes of the much wealthier and more tourist-friendly Venice urban area, Daniele seems doubly ostracised, obsessively circling the other racers but never making much of an impression. In the absence of community, the act of competition becomes a connective outlet. Only winning matters, whatever the costs.

It is from this sense of sublimated, often-sexualised frustration that Ancarani starts. Having observed the speed-boaters over multiple years, Ancarani looked to create a film that reflected the reality of their lives. In interviews, Ancarani has said that when he first saw these young men in their boats and asked about them, “Venetian people told me they should not exist.” Like the night-racers of suburban custom car culture, these speed-boaters find solidarity in a shared rejection of good taste, safety, and legality, creating an informal community out of a desire to embody values that mainstream society does not want to endorse. Atlantide starts from this position of alienation, acting as a portrait of an underclass making every attempt possible to frustrate the ruling class’s desire for them to remain invisible. Working with the equipment available to them and within the topography of the geography they inhabit, they jet through the city canals by night, showing off their boats’ ornate decals and custom paint jobs, flashing technicolour lights, blasting crass EDM from bass-boosted sound systems, and generally making as much nuisance of themselves as they can.

Like Crestone, Atlantide conjures a narrative from a real-life situation, but in Ancarani’s film, the process of fictionalisation is more overt, with more clearly defined, often deliberately unrealistic plot points inserted in between the non-narrative scenes that serve to generate a sense of place and character. Like Hertzler, Ancarani refuses to over-elaborate anything in the film, leaving regular room for interpretation by leaving contextual details out of his setup and avoiding over-explanation of the character’s backgrounds or motivations. Instead of focusing purely on the mood established through the film’s evocative visuals, the filmmaker lets a viewer make the logical leaps about any possible meanings of each image. Ancarani’s style is brash and heightened, resulting in imagery that is flashy and often deliberately obnoxious. Venice is a city of symbols, and Ancarani makes great use of its winding canals and watery vistas, making striking contrast between the historic architecture and the kitschy vehicles and the sun-soaked, hardline bodies of their drivers. Skirting the strange space between over-stylised tackiness and classical beauty, the hypnotic and near-omnipresent synth score pushes a film that—with its flashing lights, radiant colours, and sharp, hi-definition digital cinematography—is all intensity into the realm of ethereality.

Despite this surface hyperreality, Ancarani disguises his method throughout, adopting a traditional observational visual grammar and letting a viewer decide what is fictionalised and what should be seen as more broadly representative: what could have come from the actor’s own experiences and what has been invented for dramatic effect. The characters all play versions of themselves, and the sparse dialogue is supposedly drawn from their real conversations, or at least written to emulate a style they would use. Working without a script or a daily shooting schedule, devising scenarios alongside his collaborators much like Hertzler did with her companions, the final form of Ancarani’s film is unexpectedly narratively cohesive, a simple tragic arc that builds gradually towards two explosive finales, with one sequence showing a crash and then another displaying its otherworldly aftermath.

Despite the glossy thrills and all the shimmering imagery, Ancarani’s depiction of this socioeconomically-specific machismo subculture is a relentlessly bleak vision. In a different interview, Ancarani said that he is “fascinated by this generation of young people who seem to be drifting along with no sense of future.” Atlantide shows a clan of subjugated outsiders lashing out at each other in the absence of any easily identifiable oppressor to direct their anger towards. These are doomed men who know that the inevitable conclusion of a continual desire to go faster is a fatal collision but who can see no reason why they should slow down. With characters in their mid-twenties who should now be men but all still act like boys, both Crestone and Atlantide are films about how the disruption of linear time can facilitate a suspended adolescence. In Crestone this escapism results in something resembling happiness, but in Atlantide it ends in misery. Both films show the lives of a group of young alienated working class white men existing on the fringes, clawing what they can from a world that they perceive as having rejected them. In Atlantide, the men display no fear of death because they have no real love for life. In Crestone, the men have no concerns about the future as in the here and now they have each other.

Both films screened at various major film festivals. More information about Marnie Ellen Hertzler’s work can be found here. Crestone is available to rent via various digital platforms internationally and is available on Blu-ray and VHS in the US. More information about Yuri Ancarani can be found here. To receive more articles like this, do subscribe to nonlinearities. The writing in this newsletter will always be free-to-read, but donations are very welcome.