10: Nowhere Near

On Miko Revereza's Nowhere Near (2023), and on leaving one home to find others.

“No one has homes these days, yet everyone is still trying to find the next one.”

Long in the works and longer in the mind, Miko Revereza’s Nowhere Near (2023) is a film about journeys: the journeys that people take, and that memories and familial myths take. But also that a film takes—from conception to experimentation to completion, at which point another journey begins as it is met by audiences whose own journeys inform how they receive and process it. Combining footage filmed over multiple years in cities including Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York, Manila, and Oaxaca with narration from the filmmaker, Nowhere Near is an essay film primarily about migration: about moving away from one home and discovering others. Having lived undocumented in the United States for twenty-six years, after moving to Los Angeles from Manila as a child, immigration is understandably a topic that has been central to Revereza’s work to date, which has materialised in the form of assorted writings, several short films, one solo-directed feature (No Data Plan), another co-directed with his partner Carolina Fusilier (The Still Side), and this, his second solo feature and a film which seems to close a phase, spanning Revereza’s departure from his childhood home in United States, his arrival at his ancestral home in the Philippines, and his creation of a new home in Mexico.

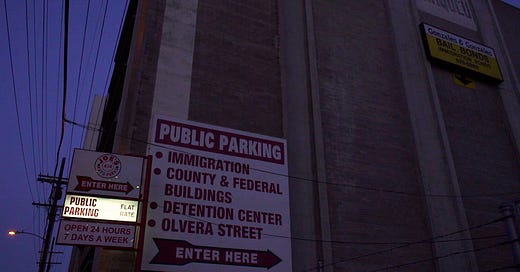

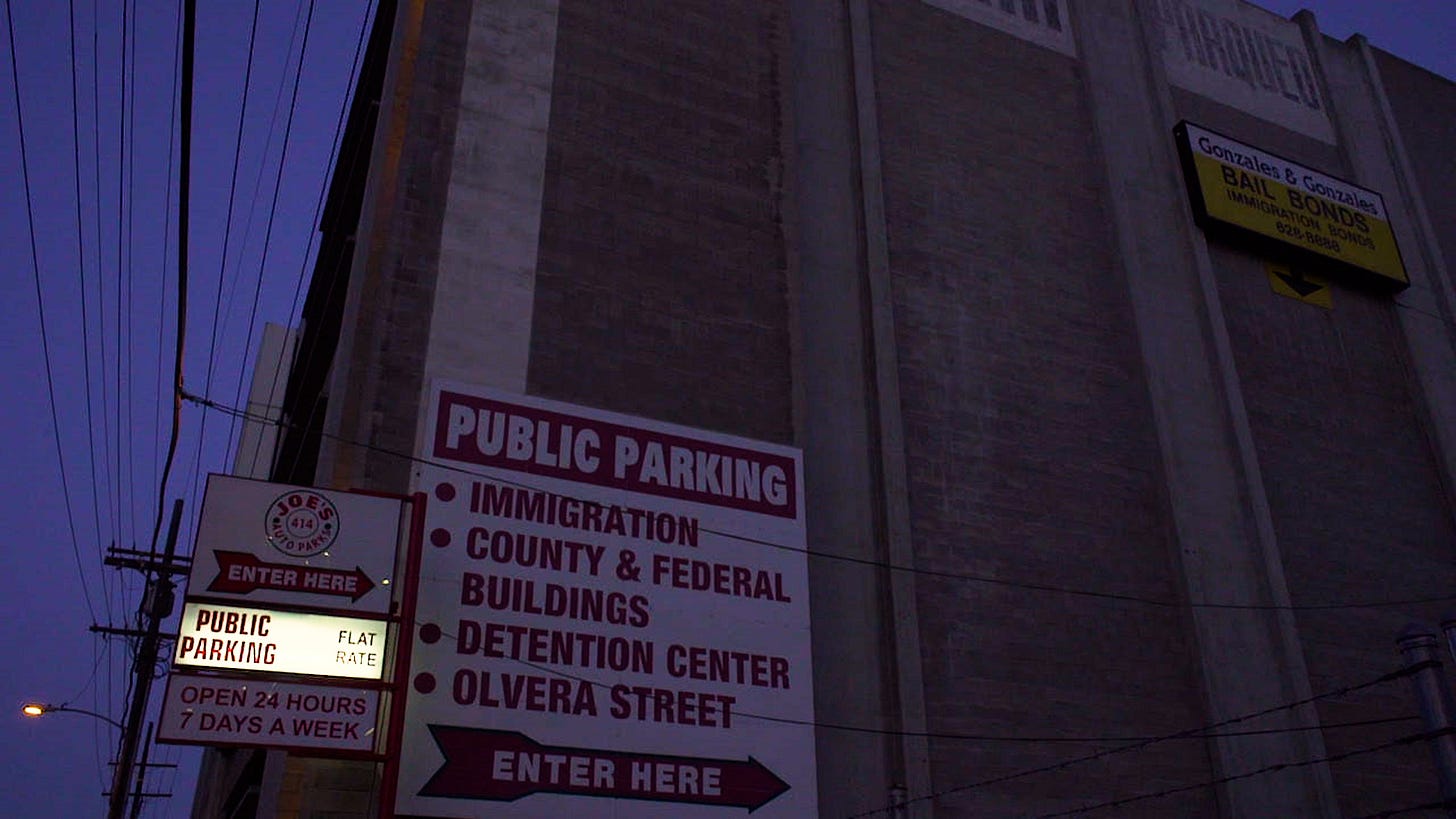

Connecting these and other places and periods, Nowhere Near assumes an episodic form. Loosely divided and not presented entirely chronologically, the film wanders. It begins in the United States, wherein Revereza introduces his family and contextualises their legal situation through analysis of the destabilising effect of 9/11 on US immigration policy. Revereza then heads to the Philippines, where he and his grandmother unearth various ghosts of the country’s colonial history. And then to Mexico, where Revereza reflects on his family’s migratory history and his own journey in life. No sections conclude cleanly as there are no easy answers to the various open-ended questions Revereza raises. Instead, the film jump-cuts constantly, catapulting between phases of the filmmaker’s life, sometimes blurring borders and timelines with potent double exposures that blend geography and time.

In the film’s middle section, upon his arrival/return to Manila, Revereza sees Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away playing on television and finds in it a tidy way of framing his film. Nowhere Near, he notes, “could be transposed” into Miyazaki’s “story about an unaccompanied child migrant whose parents were lured in by the fantasy of bountiful and endless plates of food, crossing a border into another dimension,” before “getting detained” and “incarcerated in a literal pigpen.” As well as summarising his narrative, through this allegory, Revereza also permits himself to evince the pain of his experience more plainly than he has elsewhere in his work, which, to its credit, tends to favour poetic allusiveness over explicit commentary, suggesting things rather than saying them outright. Chihiro, the protagonist of Spirited Away, “maneuvers through the shadows [...] taking whatever meager job she can find under the table, working away to free her parents stuck in an indefinite incarceration.” Revereza uses the word “incarceration” twice, emphasising that to live undocumented is to live without basic freedoms that most people take for granted, and, observing how much of this allegory fits, Revereza wonders whether, like Chihiro, his family is also under some kind of spell or curse that he could somehow free them from. This, he explains, partly informed his decision to return to the Philippines, taking his grandmother with him and rolling his camera across a series of handheld scenes that roam restlessly, following her mismatched memories and Revereza’s uncertain desires. “What if there is something back there I need to find?”

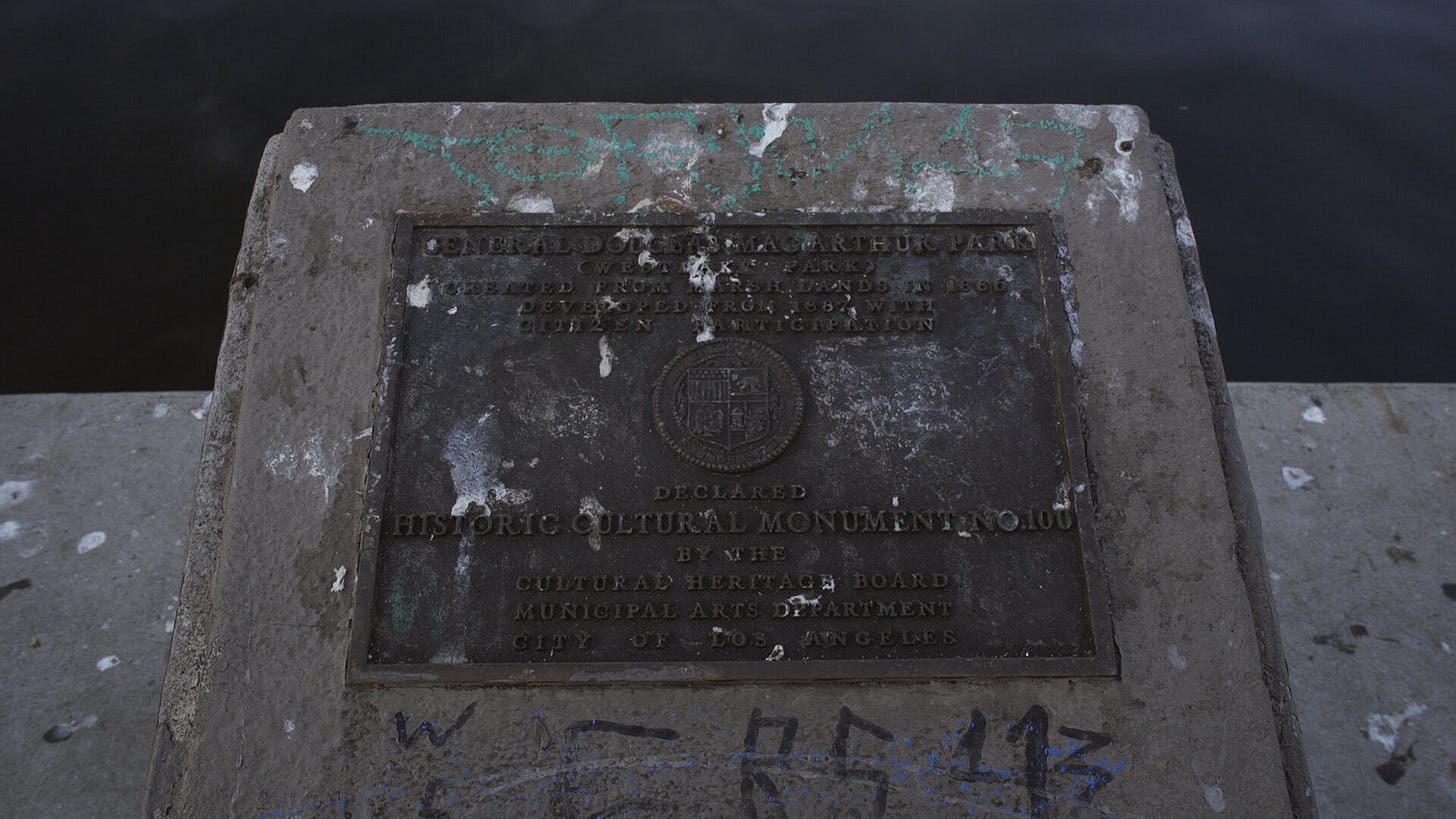

From this emerges a sort of mission narrative for the film, wherein Revereza looks to investigate this curse he believes could have been placed on his family by Spanish settlers to the Philippines hundreds of years before his birth. Through his inquiry, he hopes he can alleviate the effects, easing himself and his family from the wearying shackles of colonialism’s intergenerational weight, securing comforts (of money, time, but, not least of all, of peace of mind) that, as Revereza displays throughout the film, have been denied by the stresses imposed by the lingering impacts of colonialism in the Philippines and the trials of living undocumented in the US in the post 9/11 era and beyond. (DACA is described by Revereza at one point in the film as “practically extortion with Obama’s smile upon it.”) This, along with his grandmother’s longing to revisit various sites she remembers from her old life in the Philippines, provides a dense and multidirectional film a propulsion of sorts—a forward motion. It also gives it a natural three-act structure, which Revereza wisely resists, instead allowing the film’s form to bend and stretch as needed, chasing odd images and going on tangents.

Revereza darts around, touching upon various topics and sharing theories, jokes, and arguments, all of which contribute to developing a clearer picture of his family history and the social contexts that lie unwelcome in the background. In the film, Revereza manages to forge together material that is formally inventive and visually interesting, but also additive to the situational story he fleshes out, contributing something revealing about either the personal, the political, or both. In early scenes, Revereza and his grandparents’ rifle through family photos and portal their way around Manila on Google Street View, looking at the changes to the land in which they used to live, using technology to maintain and reawaken dormant memories and emotional ties in a way that Revereza often does with his filmmaking practice. (In Disintegration 93-96 (2017), Revereza talks over footage cut together from old home-movies; No Data Plan (2019), filmed on a cross-country train journey with a handheld camera, is interrupted by text messages from his mother that add context to the un-narrated film.) He shows a series of photographs of his grandfather holding newspapers aloft with the publication date in view, taken annually to send to his Philippine pension provider “as proof he is still alive,” and another set that includes various haunting group photos with odd heads cut out, apparently used as headshots for green cards that were never granted, lost in what Revereza later describes as a “crowded rejection bin” containing the millions of applications that were “hastily decided” during the xenophobic frenzy of the early 2000s peak of the so-called War on Terror. (“You know that war was on us too, right?” Revereza says, wearily.) Afterwards, Revereza converts a family tree sketched on a bank envelope into an elaborate computer-made “spatial model” in which his extended family’s migratory movements are shown as a series of outwardly expanding “concentric circles” instead of the traditional two-dimensional tree, an aptly nonlinear, distinctly Reverezian way of displaying the distances between a connected group of people but also how they remain linked and invisibly bound. In each fleeting image in Nowhere Near, diaristic immediacy is combined with an attempt to expand the non-fiction form.

Later on, Revereza includes a short scene in which he interviews his mother “talking heads style.” Staging her “sitting in a chair like one of those PBS documentaries,” he remarks that if this scene seems like “an outlier” from all the other “whooshy experimental stuff,” this is because he wants to “get the story” of why his family was undocumented for so long “on record” in his film. Showing both Revereza the filmmaker and Revereza the son, it is a moving scene, but also an integral one for demonstrating the impossibility of finding rational explanations for the hostilities of nation-states and the abstractions of the bureaucracies that buttress them. During the interview, his mother mixes up 9/11 and 7/11, a mistake that embarrasses her but also humanises her; it is the sort of moment of unfalsifiable realness emerging out of a structured scenario that other filmmakers might omit but that Revereza cherishes. Revereza gets no satisfaction from his interrogation, but when his mother tells him about Popkin, Shamir & Golan, the legal firm his father was working with to secure a green card, it sets Revereza off on a sub-quest in his mission, which also acts to probe at the difficulty of making the kind of film that Revereza wants to make within existing frameworks, exposing the shortcomings of traditional documentary form.

Stalking out the legal firm fruitlessly, Revereza says he had planned to “go full investigative journalist” but “instead just stood in the lobby like a punk ass with a camera.” Like his mother’s slip-up, this shortcoming only makes Revereza more relatable. Revereza is not an investigative journalist, and maybe not even a documentary filmmaker in the strictest, most restrictive sense—as the infamous Jean Marie Straub adage goes: “What does a film have to do with documents? Who uses documents? The police!”—but, instead, a filmmaker undertaking a journey of self-investigation. Kicked out of the lawyer’s office by a security guard, Revereza wanders the nearby streets “trying to catch some notion.” If Nowhere Near is a journey film, then, much like life, it’s a journey that hits a lot of dead ends, but it is in these blockades that Revereza’s sensibility crystallises clearest: searching, shooting, self-reflecting, and landing upon something genuine as a result. “Places like this make Mama nervous,” he says. “Suits and haircuts like this make you seem like you got a job that requires you to be a legal US resident, and we never had that kind of access.” Idly filming the concrete walkways and glass towers of the business district, he chances upon some “street vendors that sell office clothes.” In this strange image of a rack of ready-to-wear suits, he lands upon a fitting metaphor for living undocumented and the costs of constantly navigating an imperilled position of access—easily revoked. You walk around wearing a suit that never quite fits but that you hope still permits you to move undetected.

Nowhere Near is made entirely in the first person, but by the conclusion, Revereza opens the film out more, inviting interpretative readings of the images’ meanings by avoiding the more leading narration seen in the film’s first two thirds. Throughout, on-screen textual footnotes—the most memorable of which sees a Mobb Deep quote that reads “as long as I live, I’mma live illegal” placed over a shot of the 9/11 memorial in New York—add an extra layer beyond Revereza’s essayistic narration, offering jumping-off points for alternative lines of inquiry that run parallel to those which the narration follows. In one scene in the middle of the film, Revereza says that the cut is “where images are put together” but also “the line where they are fractured.” Through editing, a filmmaker can create jumps in space-time that act as “bridges or borders” from “one image onto another,” and in the case of Revereza’s film, also between people, places, and whole periods of lived experience and time. “An edited film is an assemblage of wounded parts,” Revereza explains, a cinematic surgery of sorts. “You have to fracture the footage to put it back together,” but sometimes the various composite parts “just want to remain fragmented,” like a transplant that doesn’t take. No amount of formal ingenuity can find sense where there is none, or force together irreconcilable things that want to remain apart. If he cannot ultimately bridge distances in a world damaged by the violence of borders and the brutality of states, Revereza can at least find beauty in the interstitial moments and in-between spaces between here and there, then and now, far and near. After a lingering shot of Revereza’s arm, pen in hand, flitting fitfully over a printout of the film’s narration that seems to subtly emphasise the difficulty of process, of self-knowledge, of speaking for others, and of achieving authenticity in a work so inherently personal, Revereza abandons verbal language altogether, ending Nowhere Near with an extremely moving un-narrated montage of a type that is interjected throughout the film.

Accompanied by the film’s intermittent soundtrack which mixes jangly, noodly guitar twangs, gentle, emotive piano, and expressive improvised clarinet (the latter of which, with its breathless splutters, discordant squarks, and guttural mini-screams, was, according to the credits, performed by the filmmaker himself), countless images float by. Revereza’s grandfather, the Los Angeles streets, the blue sea, a dragonfly’s wing, some crabs in a tank, water and a window, Revereza’s mother, his father, rows of bottles on a supermarket shelf, a hand reaching out, his brother in profile. As Revereza explains when defining editing, cuts can go “from A to B, B to F, G to X,” and this is exercised in this final montage, bridging “broken timelines” and unifying past, present, and future together in a wash of beauty and tranquillity. Cymbals shimmer on the soundtrack and the credits roll. After all the pain of distance and division, Nowhere Near ends with something else, not didactic, or even linguistic, but more simply expressionistic in its combination of image and sound. If not exactly suggestive of closure, this wash of record-making and remembrance, of familial legacies and personal memories, seems to at least evoke something resembling peace.

Miko Revereza's Nowhere Near (2023) had its world premiere at Open City Documentary Festival, and then will screen next at TIFF and NYFF. More information about Miko Revereza can be found here, or here. To receive more articles like this, please subscribe. The writing in this newsletter will always be free-to-read, but donations are very welcome.

Poète... vos papiers !