13: Anachronic Chronicles: Voyages Inside/Out Asia

On Pan Lu and Yu Araki’s Anachronic Chronicles: Voyages Inside/Out Asia (2021), and on the meaning of making home movies.

“Today is the memory of tomorrow”

The proliferation of smartphones has meant we no longer think much about making home movies. The technology needed to record memories is always in our pocket and the act of capture is an unplanned and unthinking one: point, shoot, then distribute for instantaneous consumption and reaction. However, from the 1920s through to the 2000s, filming the family was a more calculated and conscious act. The amateur filmmaker had to want to film and also had to have the means to be able to, which meant buying equipment and learning how to use it. There was also more intentionality in taking hold of a camera made for the explicit purpose of making moving images, rather than having a device that captured them as a secondary capability. And, even if it wasn't always latently expressed, the individual filming their family had ideological intentions or narrative impulses that informed their filming decisions or dictated the moments they chose to pick up the camera or bring it out somewhere with them. As a result, if not necessarily an artistic act, making a home movie always meant something.

Pan Lu and Yu Araki’s essay film Anachronic Chronicles: Voyages Inside/Out Asia (2021) explores what it means to make home movies, seeing what can be found out about ourselves and our societies when we look closely at our family footage. Analysing various fragments of home movies and archival images—some, such as slide film from Taiwan in the 1950s and 8mm footage from Hong Kong in the 1960s, not showing their family, but most, filmed on Hi8 video in the 1990s, across Japan, the United States, and China, featuring their own loved ones—the two artists work, through remote, pandemic-period audio dialogues and intermittent quotation, to unpack the meanings of home-movie-making in a specifically East Asian context, focusing on a shared moment when the two filmmakers, now in their thirties, were both young and their lives were at a point of transition.

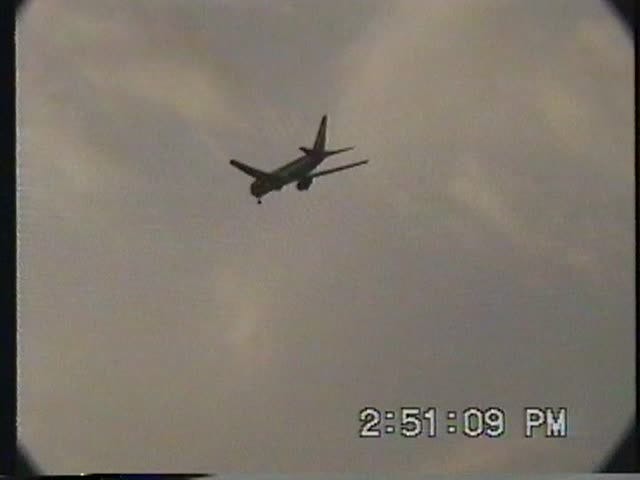

The film opens with a crackle of celluloid, followed by a flash of videotape fuzz. We then see an image that, due to the date stamp in the corner that was a fixture of consumer-grade home video, is immediately telegraphed as being from a home movie from the 1990s. A man in a sweater vest is seen sitting cross-legged on a bed, framed inside a circular mirror. He waves and the camera zooms in on his face, before going back further out to momentarily reveal the operator, a young boy we later learn is Yu Araki, followed by a whip pan and a cut to black, after which the film begins. “You are filming yourself,” says the grinning man, revealed later to be Araki’s father. Despite lasting only 30 seconds, it's a sophisticated sequence, displaying a kind of accidental complexity indicative of the sorts of home movie material that the artists fixate upon in their analysis. In this strange breaking of the fourth wall, both the camera operator and its subject are amused and excited by the possibilities of image-making with the then-nascent Hi8 camera technology. The adult Araki observes himself as a child engaging in an act of self-documentary, unaware that, decades later, he would find himself extending this same impulse in a film reworking this footage.

Footage early on in the film from Lu’s archive shows a similar aesthetic exploration. A range of faces are seen in awkward roaming closeups at a family gathering. Lu observes that the adults seem to freeze when faced with the camera, posing the same way they would for still photographs, whereas the children move around constantly, meeting the medium intuitively on the level of functionality, uninhibited, unlike the adults, by pride or self-awareness. Two other sequences display the same playfulness which is a large part of the appeal of home movies. In one, filmed by Araki’s father, a precocious Araki plays “Let It Be” by The Beatles on piano while his brother armpit farts as accompaniment. In the other, Araki, this time with free and unsupervised access to the camera, creates a short narrative using Lego vehicles, a sequence he reflectively recognises as his first film as director. These moments mirror much of the material that follows, wherein the family can be seen to be first exploring how the camera works, before then beginning to think more about what image of themselves they want to project to any potential viewers. This is then compared with what, when closer attention is paid, the images actually reveal about the people and the period, as well as more broad ideas about home movie-making in Asia and what the filmmakers call the “‘anti-spectacle’ power of folk images.”

Lu and Araki divide their essay on home movies into four structured parts. The first, which includes these playful parts, shows the idea of home video as a novelty, examining the accidental aesthetic preoccupations and experimental techniques that emerge from tinkering with new technologies. The second looks at the idea of boredom, challenging the received wisdom that home movie footage only remains of interest to those directly involved in its making. The third section explores nostalgia and sadness, looking into what it means to watch yourself from a distance, forced to reckon with time’s passing and the process of ageing or to see loved ones who are no longer living immortalised on video. The final section looks at the anthropological value of home movies by exploring ideas around gender and representation in relation to the medium, as well as how matters of social and cultural importance can be preserved in home movies, sometimes unwittingly. Throughout these sequences, the two artists share images and ideas back and forth, reflecting through dialogues that, while philosophical in nature, come across more as a conversation between two friends than a structured intellectual exercise—more chat than lecture. For instance, one of the most poignant observations comes out of nowhere when Araki says that his poor memory means he cannot distinguish between real recollections and the videos he has been reviewing. “As I watch,” he says, “I feel that my memories are starting to be replaced,” almost as if moving images can tape over the brain’s own visual database.

Another memorable sequence is in the section focusing on the anthropological value of home movies which sees Lu reflect on watching a Chinese dubbed version of the US home video compilation show America’s Funniest Home Videos, and comparing the differences between the sort of slapstick material that features in this programme with the “more serious” subject matter of home movies filmed by Asian families. “I don't think that in China we would shoot these kinds of footages,” she says, right after an analysis of material from her own archive that features a restaurant dinner wherein family members discuss what she calls “migration strategies”: serious and practical topics such as where to move to make the most money and provide their children with the best education. In a later exchange that evinces something similar, Lu comments on the gendered nature of home-movie-making. Because fathers traditionally are the ones interested in new technologies, home video, she argues, became not only “the realm of fathers” but also a place for a father to register a “good picture of his family” into the annals of private history. A byproduct of this is that the men themselves are rarely ever seen in this distinctly subjective form of documentation.

Breaking up the themed sections, the artists include reworked quotations from several texts, read aloud in Shanghainese, Taiwanese, and Japanese. Some come from the contemporary Shanghainese writer Ag. Others are from short stories originally written by Japanese authors in the 1920s and 30s, later translated into Chinese by the Japan-based Taiwanese writer Liu Na’ou. Interestingly, rather than directly quoted, these texts were cross-translated using automated translation software and then adjusted to abstractly speak to the film’s themes. The use of these texts, and the references to them in the conversations, while slightly opaque, adds layers to Anachronic Chronicles, achieving what Lu describes as an expansion of the project beyond the filmmaker’s personal relationships “to a wider scope of East Asia and its migratory aspects,” as well as the creation of a representation of the “fluid, trans-nationalistic nature of our generation and times.”

One of the key focuses of Anachronic Chronicles is migration and diasporic experience. The reason the footage in the film exists is because Araki’s father and Lu’s uncle both bought Hi8 cameras to capture migratory journeys; Araki’s father had decided to move from Japan to America, and Lu’s aunt and uncle from China to Japan. The film’s final sequence embodies this theme most pertinently. Young Araki films from a car backseat as the family drives along a nondescript American highway, encountering various Chinese storefronts, and, through being able to recognize and read certain characters on the restaurant signs, experiencing a kind of familiarity. “Hey, are we in China?” asks Araki’s brother, which causes the family to burst into laughter. It makes for a touching conclusion. The young Araki in the footage is experiencing a kind of inbetweenness, between Asia and America. And in the reviewing of this material, thirty years later, the adult Araki is then presumably going through something similar, psychically drifting between the here and there of his birthplace of Japan and homeland in America, but also between the then and now of the temporality of the analogue video and its revisitation in the digital present. Looking over this sort of material from the distinctive vantage point of 2020, a period where, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals were deciding to digitise family footage, Lu and Araki create a film that feels like the ultimate pandemic document. In it, the two artists revisit old footage to reach new conclusions, overcoming the stasis of that moment by travelling via teleportation, while also addressing the sense of isolation too. By communicating with each other through words and images, they forge connections across countries, cultures, and time, creating something reflexive and reflective, and both universal and personal in its mix of contemplation and introspection.

Anachronic Chronicles: Voyages Inside/Out Asia (Pan Lu & Yu Araki, 2021) had its premiere at London Film Festival. You can watch a teaser here. More information about Pan Lu can be found here, and about Yu Araki here. To receive more articles like this, please subscribe. The writing in this newsletter will always be free-to-read, but donations are very welcome.