14: In the Manner of Smoke / Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued

On Julian Castronovo’s Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued (2025) and Armand Yervant Tufenkian’s In the Manner of Smoke (2025), and on essay films as attempts and efforts

“Who lived here?”

“I want to tell you a story, or perhaps a number of stories,” says the narrator enticingly at the start of Julian Castronovo’s Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued (2025), “each marked by moments of strange mystery and coincidence.” Intersecting stories, ideas, images, objects, and textures are at the centre of this film, and also of Armand Yervant Tufenkian’s In the Manner of Smoke (2025), another essayistic first feature with which Debut shares several commonalities. Both mystery stories of sorts, these are essay films that embody the etymological roots of the word essay—coming from “essai,” the French for “an attempt” or “to try.” They are films that are endlessly searching and stretching, and the narration in both could justifiably be described as “pretentious.” Sometimes strained, the speakers can feel like they are trying a little too hard—clutching for something always remaining just beyond reach. But, following Dan Fox’s reclamation of that word in Pretentiousness: Why It Matters (2016), being charged with pretension isn’t necessarily a criticism; it can be something to celebrate—a sign that risks were taken, that an attempt was made not just to replicate that which already exists but to strive for newness instead. What is the point of making an essay film if you are not going to try?

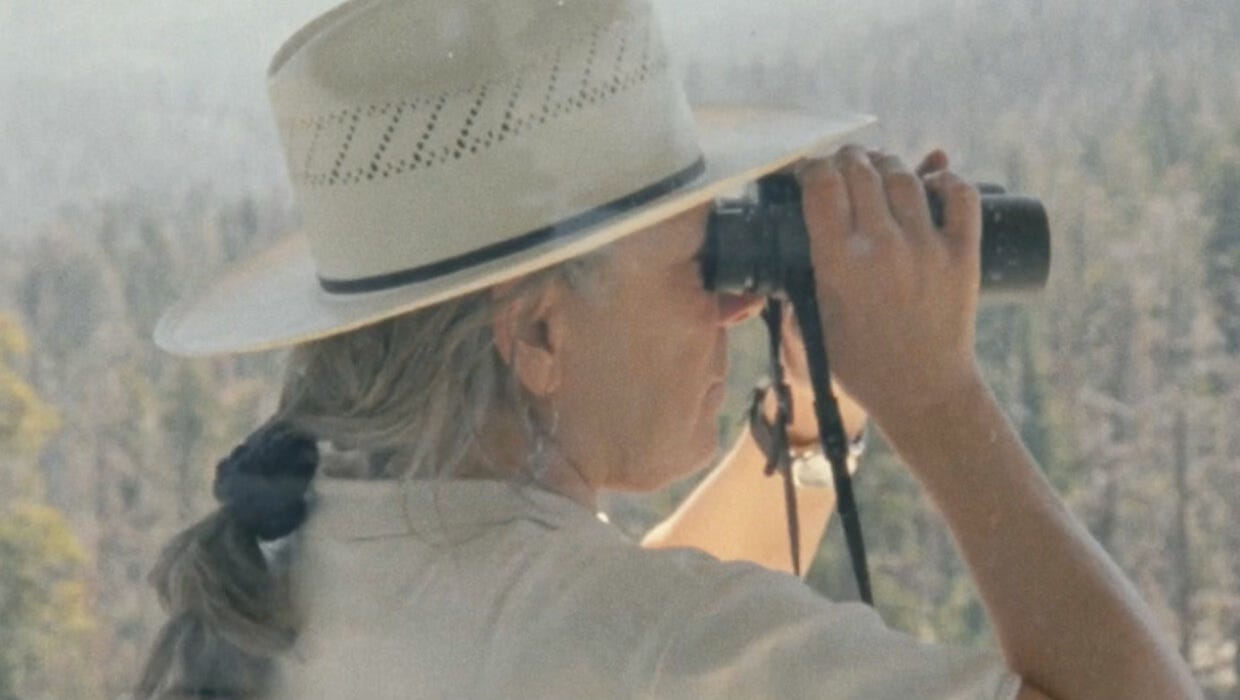

In both films the filmmaker is present, anchoring the film with the fixity that a protagonist provides but also enabling an exploration of performance and persona. And both filmmakers put form pleasingly at the forefront, examining the various elements of filmmaking and unpacking their functions. The attempts of both filmmakers are multivalent but they each have an ostensible subject—a starting point. In the Manner of Smoke begins with forest fires and Tufenkian’s film is structured around the idea of the lookout post, opening up an investigation into images and looking more generally. First, in the Sequoia National Forest in California, we are introduced to Mich Michigian, an experienced fire lookout that Tufenkian is working under. By her, he is taught how to look (with his eyes, but also the camera), how to speak (using the radio code communication system of “Clear Text”), and how to be alone (staying sharp over long periods of solitude)—all of which, of course, are skills of benefit to a filmmaker aiming to make an essay film. Parallel, in London, we meet Dan Hays, a painter who is seen producing a series of pointillist paintings of the “Rough Fire,” a major 2015 wildfire in the area, that were commissioned specifically for the film. Painstakingly recreating webcam-captured photographs of the fires, he uses small square brushstrokes that fill out the canvas cumulatively, building out a triptych of reproductions, or rather reinterpretations, of the digital source images pixel by pixel. Seen up close, they only resemble abstract expressionist washes of pastel colour, but when observed from a distance they form recognisable landscapes. The film then pivots between these two locations, mixing crystalline 16mm material and low-resolution digital imagery, as well as moving and still images, blending the visible and the invisible, the digital and the analogue, the imagined and the real.

Somewhere, a third strand is introduced in the form of a shaggy dog story about Tufenkian’s search for a mysterious woman in the town of Fresno. The three strands develop gradually and elusively in slow cycles, never quite converging into anything concrete or conclusive, instead transitioning one scene into another, diffusing much like the title’s smoke. Tufenkian’s poetic narration is wandering and coded, and the film can sometimes seem difficult to get a grasp of. Given the subject matter and themes at play—this smoky form—this is most likely by design. Tufenkian talks aphoristically, saying slightly wispy things like “what the fire promises, it will provide,” but never quite directly unpacking any of the complex ideas his film is gesturing towards. Hays completes his triptych. The detective story trails off after Tufenkian’s search reaches a series of dead ends. Tufenkian stops working at the lookout. The strongest throughline in the film is its pronounced study of textures and surfaces, making for a gorgeous gallery of patterns, grains, patinas, and gradients of all kinds, not to mention the various statics, crackles, and other kinds of smoke-like fuzzy sonic textures. From the film’s opening shot, which shows a rising grey vapour that moves glacially across the frame accompanied by near-ambient radio chatter, to several late film images that show a pixelated sunset slowly receding, images of pure beauty are the focus of the film, included both for their sublimity and their inscrutability, their refusal to be read as only one thing. An intermittent soundtrack of orchestral music by John Luther Adams, whose compositions are inspired by nature, and Tōru Takemitsu, famous for writing scores for Kenji Mizoguchi and Akira Kurosawa, furthers this double sense, lending proceedings a feeling of the divine and unknowable. The film feels like an exegesis of the benefits of close examination but also an admission of the impossibility of this study reaching anything resembling full understanding. This is embodied by the protagonist’s attraction to a line of work that involves nothing but looking, his struggles with that work’s realities (a passivity that is inherent to looking but not acting), and the eventual reveal that this work has now since automated, the human gaze replaced by the all-seeing eye of the digital camera.

Given the recent fires in Los Angeles, and the continual relevance of the subject matter more generally, In the Manner of Smoke feels timely. Made between 2018 and 2025, though its form is quite contained and its style minimal, the film’s purview is significant; over time it becomes a kind of slow-building epic of the essay film form, an understated film that feels maximalist as a result of its grandiose score and painterly imagery. The film’s title comes from a Leonardo da Vinci quote. Describing his sfumato technique, wherein the blurring of paints are used to create texture and volume, da Vinci explained that “light and shade should blend without lines or borders in the manner of smoke.” This is of course what happens in Tufenkian’s film. All sorts of things are brought adjacent to each other and then smudged so that what divides them becomes indistinct, no longer detectable. Various images hailing from different geographies, created in different mediums, holding different meanings, are, in a manner that Tufenkian describes in his website’s description of In the Manner of Smoke as “an ecology,” gathered and blended. As a result, many disparate but interlinking things are brought together, and made richer through comparison and contemplation. A film of light touches, soft brushstrokes, blurred pixels, and slowly dissipating gasses, In the Manner of Smoke is the kind of film that benefits from multiple viewings, too full of elements and too withholding in the way that it presents them to be adequately absorbed in a single sitting. Given the da Vinci reference, the film fittingly ends on a painting, one that seems to reinforce this idea of the fundamental inscrutability of images and the unknowability of the signs and symbols they act as containers for. We see a tableaux painting on a wall, Piero di Cosimo's The Forest Fire. Painted circa 1505, it is a panoramic scene showing various animals fleeing a blaze. Tufenkian then zooms in on each animal individually, showing their frightened expressions, frozen forever in fear, before holding the camera’s attention on one particularly strange looking creature, a pig with the head of a satyr, for what feels like far too long, eventually fading to black. The film ends and we are left wondering what we are looking at and what it is supposed to signify, enjoying the pleasurable frustration of trying to solve a particularly cryptic crossword puzzle.

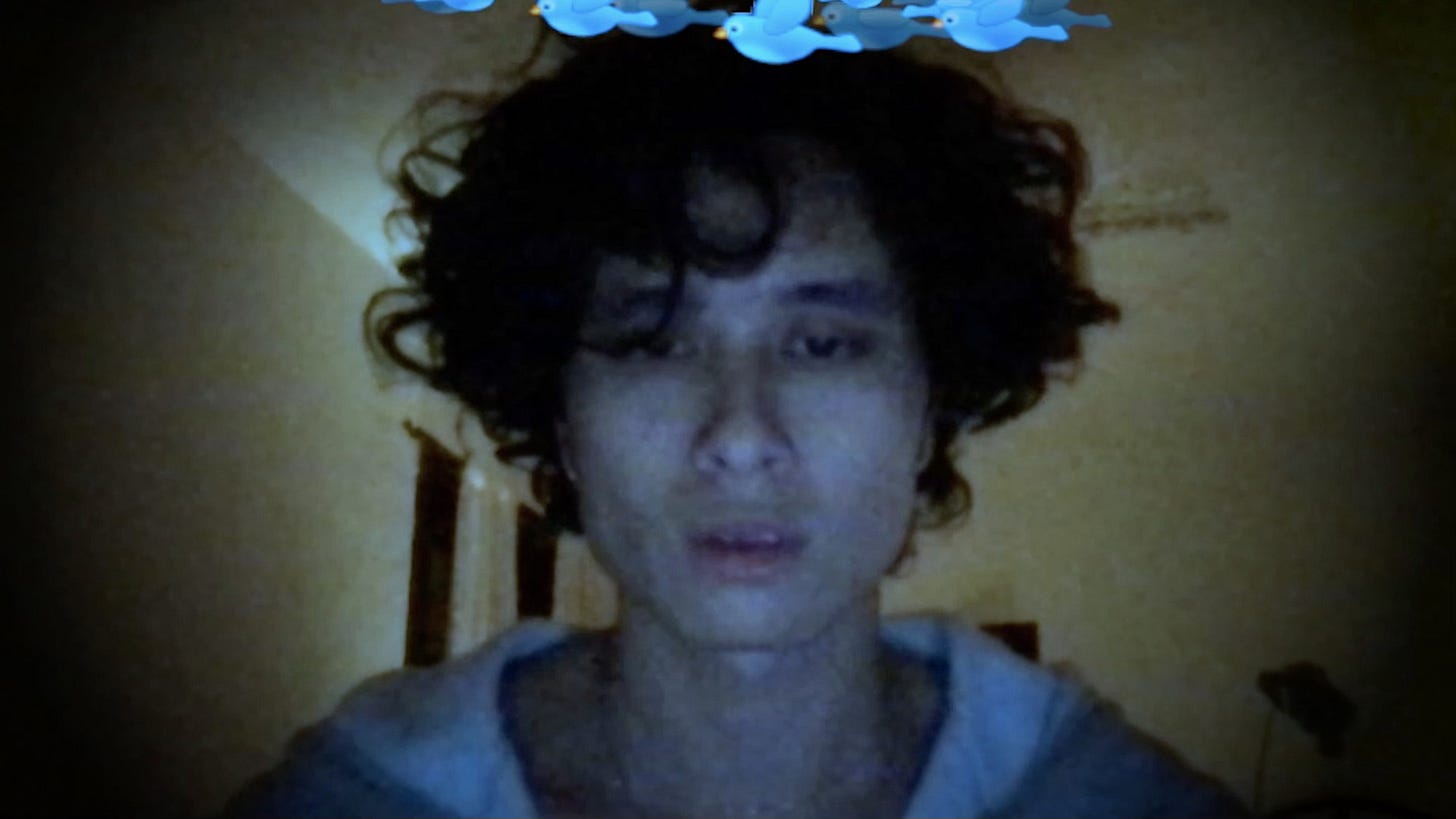

Debut, a comparable but much more playful film, arrives at a similar place by following a different set of routes. The central thread of Castronovo’s film is the search for an art forger, which instigates a wider investigation into art, authenticity, and representation, and, ultimately, the futility of looking for concrete meanings in contexts that can never provide simple clarity. The Long Goodbye-style detective story structure that is one element of Tufenkian’s film is in Debut the primary thrust, providing what one of Castronovo’s film’s three narrators calls “a linear narrative framework of events and consequences” that in their accumulation make for “a movie about crimes and art and images.” The film’s unravelling form mimics the approach of literary postmodernists like Jorge Luis Borges or Thomas Pynchon, adopting a metafictional hard-boiled narrative that constantly folds in on itself, spiralling off in diverging directions, dancing joyfully down different avenues, introducing and then leaving new jokes, images, or ideas dangling. The story begins with a cascading series of artefacts (the reverse of an iPhone, the front and back of a matchbox, a key, a punnet of cat food, a vape) that are presented as flat, on-screen objects, scanned and cycled through—in what appears to be a sendup of the pervasive non-fiction aesthetic trend of the display of white documents on a black background—as if they are evidentiary images shown on an overhead projector. The significance of these objects is explained by the film’s first narrator, an archivist figure voiced by Phillippa James, who talks about the young filmmaker Julian Castronovo in the past tense, establishing the film’s backstory like a pathologist conducting a post-mortem. The Castronovo character, the second narrator and a version of the filmmaker, after a while speaks for himself, mostly through a series of shoddily lit, perfectly pitched confessional webcam-shot faux vlogs. And a third, French-speaking narrator, voiced by Rebecca Benoit, also appears later still, bringing a different tone and tenor, and adding another layer to a film from a filmmaker who derives fun from stacking the elements.

We are told that Castronovo, upon moving into an apartment in New York, came across a letter addressed to an unnamed previous tenant. From this he attempted to track down the recipient, believing them to be a prodigious art forger named Fawn Ma, who trained in Dafen, the famous village in China renowned for its production of massive volumes of highly technical imitation oil paintings, before moving to America and creating a small body of original photography and performance art. This search takes him to Los Angeles, where, as a result of an ill-thought-out stunt involving the production and circulation of fake movie studio business cards, he meets a film producer. Castronovo pitches them a true crime film about a filmmaker tracing a mysterious art forger—so Debut, or at least a version of it—and he is told that, in the world of film financing, “it’s only possible to make a feature film if you’ve already made a feature film.” The need to solve the mystery then becomes an impetus for the making of the film, and also a motivation for the Castronovo character, presented self-deprecatingly as a listless, self-doubting chancer, to actualise the premise he has been presenting and become the filmmaker he has been saying he is. The story spirals, unfolding as much like the kinds of fanfiction found on Reddit as the more high-minded literary fiction the film takes as source inspirations—a kind of Borgesian creepypasta—until Castronovo is inexplicably contacted by a mysterious financier located in the Czech Republic who asks Castronovo to visit him, setting up another mystery narrative that again gives him cause to change location.

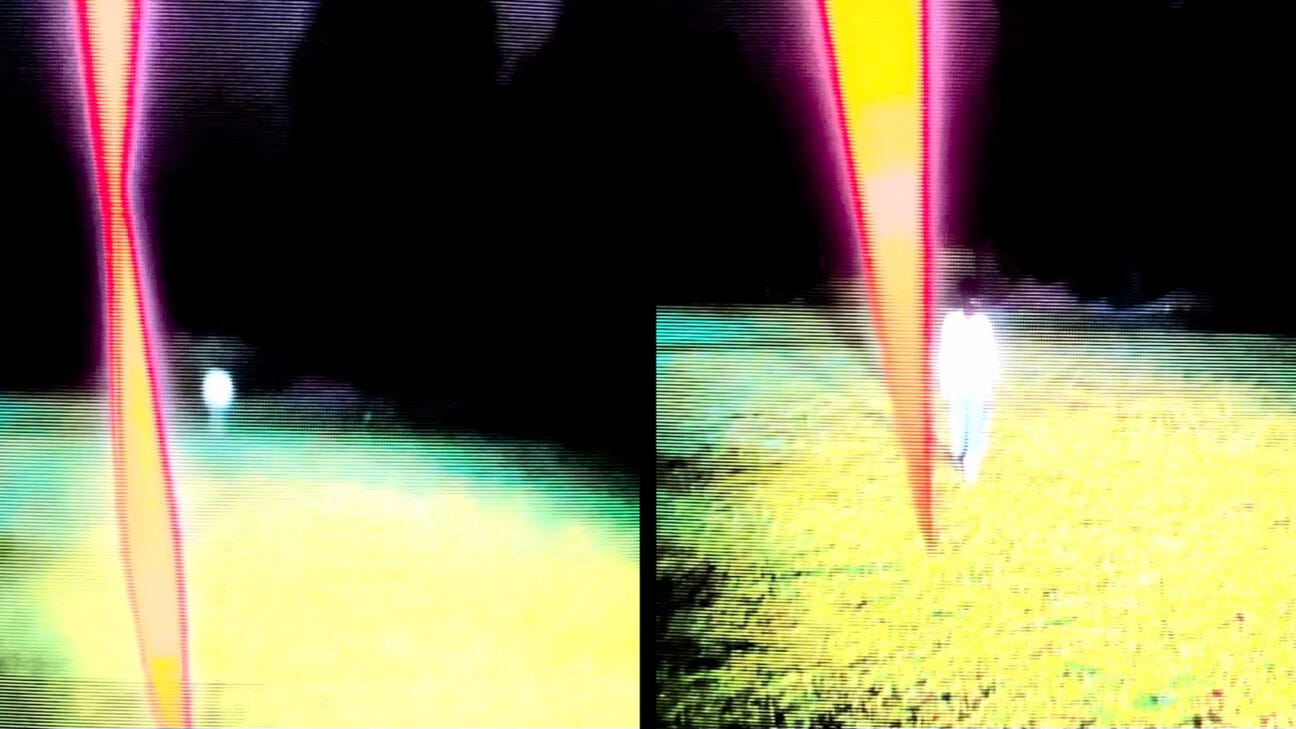

The most impressive aspect of Debut is its variety and ingenuity, and how, like In the Manner of Smoke, it explores the multitudinous of the image, finding near infinite forms to present an idea artistically, all at minimal cost and with limited resources. Flying by alongside the fast-moving narration, we see models, miniatures, puppetry, scanned documents, photographs, letters, and other print ephemera, plus varying mobile phone filmed footages, ropey computer-generated imagery, CCTV capture, various striking uses of video’s distortions, vlogs and diaries, and the kind of screen-recording stylistics familiar to desktop documentary. All of it is scrappily beautiful—an entire aesthetic world is conjured and rendered, all largely within the bedroom or the computer screen. And at some point, we are also shown Fawn Ma’s artworks too; they are absurdist performance pieces which reference Yoko Ono’s conceptual film ideas and photographs that evoke Ai Wei Wei’s “Study of Perspective” series. Within a film that is ironic, intellectual (and yes, sometimes, a little pretentious), the mimicry applied here feels earnest, a fond homage to artworks that are seemingly a sincere source of inspiration for the filmmaker. It embodies the sense of joy present in a film that while ostensibly serious is imbued with a wry sense of fun.

All this begs many questions. What, if any of this, has any basis in actuality and reality? The answer seems fairly obvious. It doesn’t matter, or, at least, it only does so in that these things are real in the sense that they were constructed. All films are documentaries of their own making, but this one is perhaps more this than most. In needing to make a feature in order to make a feature, Castronovo creates a detective story that generates the invention of a filmmaker, a process he has called “reverse auto-fiction.” This allows Castronovo to explore various ideas he finds interesting, to make pretty images, and to ruminate, digressively, on art and artifice, originality and plagiarism, the slippery lines of reality and fiction, the role of narrative within non-fiction cinema, the indexicality of the image, questions of representation in relation to the author, and more besides. But with any essay film, and especially one structured as a narrative puzzle like this, there is a lot of expectation created for a conclusion that is a satisfying payoff for all this intrigue. In the sort of metafictional narratives that Castronovo is homaging, where one subplot triggers another creating an endless mise en abyme, the journey itself is the destination, the digressions proving a pleasure in unto themselves.

In a text on the genre, Jean-Pierre Gorin wrote that the essay film is the “rhizomatic form par excellence, forever expanding and finding no better reason to stop than the exhaustion of its own animating energy.” This is a good description of Debut and In the Manner of Smoke, both of which are defined by their use of what Gorin calls “surplus, drifts, ruptures, ellipses and double-backs.” Debut reaches exhaustion eventually, and the mystery, as might be expected, remains unsolved. Instead, we are encouraged to reflect on the journey itself, the instigating force for this essayistic attempt, this treatise on trying, this testing out, teasing, and stretching of forms and techniques. The Castronovo character arrives at a point of fatigue, his digital image distorted to the point of abstraction, his voice performatively drained of emotion. “I’m tired of looking for things, tired of trying to make things,” he concludes. “Mostly I’m tired of this little interminable charade of pretending to be a person who is capable of deciphering the world.” After this, his voice cuts off mid-thought and we do not hear from him again. Our conclusion comes instead from our investigator narrator, who talks over what we are told are the last images ever seen of Julian Castronovo, a degraded, totally out-of-focus landscape image that shows a pixellated figure walking towards some indeterminable horizon. In lieu of the decisive answers that always seemed improbable we are encouraged “not to look too hard at things” but to instead “familiarise ourselves with a close proximity of infinite meaning and meaningless,” which can be found in the “oblique field of events, and the imprints of events” that were unspooled over the preceding ninety minutes. A rising piano medley plays over the sound of distant birdsong, and with it, this conclusion feels, strangely, not like a cop-out but instead a comfort. “The world is a reservoir of ones and twos,” we are told, “of little cries and echoes.” In creating himself, Castronovo leaves a trail of littered art objects, ideas, images, scraps, and, indeed, cries and echoes. These things are the film’s lasting value, not the tidy resolution of a narrative.

“Pretentiousness is interesting,” says Howard Devoto, of the band Buzzcocks, quoted by Fox in his book. “At least you’re making an effort.” In a Tone Glow interview, Castronovo comes to a similar conclusion about pretence, or at least about pretending. Asked about social media and performance, Castronova states that, for him, “‘pretending to be the person you want to be’ is a very similar activity to ‘being’ the person you want to be,” later citing the vernacular expression “fake it till you make it.” As Fox argues in his book, a little pretension goes a long way because if you never strive to be something more than you currently are, you’ll never change or grow. In the context of a creative project, without taking a risk of looking a little silly, you’ll never start the work, let alone circulate it. Castronovo continues: “I think this logic of pretending and being—that type of metaphysical game—was the point of origin for Debut. I thought that by inventing a certain type of fiction, becoming a filmmaker and making a film would be a self-generating endeavor.” To do anything you have to try something; to get anywhere you have to start somewhere.

In the Manner of Smoke (2025) had its premiere at Cinéma du Réel, where it won the International Award. More information about Armand Yervant Tufenkian can be found here. Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued (2025) had its premiere at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. More information about Julian Castronovo can be found here. To receive more articles like this, please subscribe. The writing in this newsletter will always be free-to-read, but donations are very welcome.